The vibrant, thunderous spectacle of New Year’s Eve fireworks is a universal symbol of transition, a collective deep breath as the calendar turns. For moments, skies across the globe are painted with brilliant, fleeting colors, accompanied by the crackling applause of millions. Yet, as the final ember fades and the dawn of January 1st breaks, a different, quieter picture often emerges in city squares and suburban streets. The aftermath of these joyous celebrations frequently includes a sobering layer of debris: spent casings, plastic fragments, and the general detritus of a massive public party. It is in this post-revelry stillness that a remarkable, heartening narrative has consistently unfolded in recent years, one that transcends cultural and religious boundaries. Muslim communities from Jakarta to Johannesburg, London to Lahore, have been organizing and participating in widespread clean-up drives, voluntarily taking to the streets to restore order and cleanliness after the night’s festivities. This proactive movement is not a protest against celebration but a powerful testament to a different set of principles, turning the messy aftermath of New Year’s Eve fireworks into an opportunity for communal service and environmental stewardship.

The motivation behind these coordinated efforts is deeply rooted in the Islamic concept of Khalifa, or stewardship of the Earth. Followers of Islam believe that humanity has been entrusted with the care of the planet, a responsibility that encompasses keeping one’s environment clean and pure. Littering and polluting are considered transgressions against this sacred trust. Therefore, the sight of public spaces strewn with waste, especially the residual mess from New Year’s Eve fireworks, presents a direct call to action for many Muslims. It is viewed as a civic and religious duty to rectify the disorder, to protect wildlife from harmful debris, and to ensure shared spaces are safe and pleasant for all citizens, regardless of who created the mess. This sense of duty transforms a simple clean-up into an act of worship and social responsibility, aligning faith with tangible, positive action in the community. The initiative beautifully reframes the narrative from one of blame to one of solution, demonstrating that faith can be a driving force for practical public good.

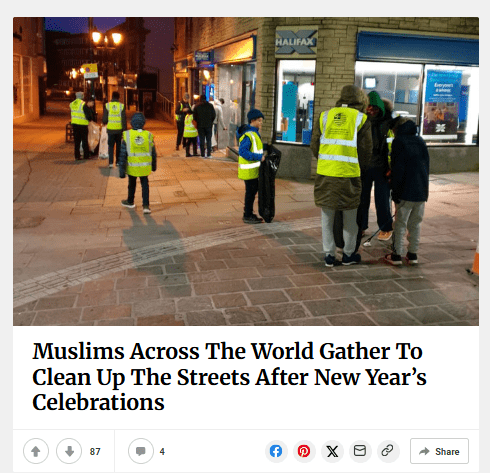

Organizing these clean-ups is a logistical endeavor that often begins well before the clock strikes midnight on December 31st. Local mosques, Islamic community centers, and youth groups utilize social media platforms, messaging apps, and announcements after prayers to mobilize volunteers. They coordinate meeting points, distribute gloves, biodegradable garbage bags, and sometimes even arrange for city councils to provide extra waste collection bins or to facilitate the disposal of the gathered refuse. The volunteers themselves represent a cross-section of the community: families with young children, groups of teenagers, and elderly individuals all donning high-visibility vests and working side-by-side. This intergenerational participation is crucial, as it instills values of service and environmental consciousness in younger members while providing a tangible, unifying project for the entire community. The operation is a quiet, efficient counterpoint to the night’s chaos, a methodical and collective effort to heal the urban landscape.

The impact of these initiatives extends far beyond the immediate aesthetic improvement of cleaner streets. Environmentally, the clean-up addresses a significant issue. New Year’s Eve fireworks debris is not merely paper and cardboard; it contains chemicals, metals for coloration, and plastic components that can leach toxins into soil and waterways. By systematically removing this waste, volunteers help mitigate this pollution, protecting local ecosystems. Socially, the action serves as a profound bridge-builder. In many Western cities, these Muslim-led clean-up crews working diligently on New Year’s Day become a visible, positive presence that challenges stereotypes and fosters goodwill. Neighbors from other faiths or backgrounds often stop to thank the volunteers, and some even join in, creating spontaneous moments of interfaith and intercultural cooperation. The clean-up becomes a silent dialogue, speaking volumes about shared values of community care and civic pride louder than any slogan ever could.

Furthermore, the movement highlights a constructive approach to cultural coexistence. These volunteers are not rejecting the celebration of New Year’s; many participate in the festivities themselves. Instead, they are addressing a universal byproduct of large-scale public celebration with grace and initiative. It showcases a model where different cultural and religious practices can coexist and complement each other. The community enjoys the celebratory aspects of the holiday like everyone else, and then contributes its unique ethic of service to handle the consequences. This nuanced engagement is a powerful statement against polarization, demonstrating that one can maintain distinct religious identities while being exemplary, contributing citizens to the broader secular society. The action says, “We share this space with you, and we are invested in its well-being,” which is a fundamentally unifying message.

The psychological effect on the volunteers and the observing public is also noteworthy. For the volunteers, the act provides a profound sense of agency and purpose. In a world often dominated by news of problems and conflicts, here is a concrete, positive problem they can solve with their own hands in a matter of hours. The physical labor yields immediate, visible results a clean park, a clear street which is immensely satisfying. For the wider public, witnessing this altruism on a holiday morning can be unexpectedly moving. It disrupts the typical New Year’s Day narrative of recovery and lethargy, replacing it with one of proactive care and community spirit. It plants a seed of inspiration, encouraging others to consider how they might contribute in similar ways, perhaps for other causes or events. The clean-up becomes a ripple effect of positivity.

Critically, this is a global phenomenon, not isolated to one country or continent. Reports and images flood social media each January 1st showing similar scenes from dozens of countries. In the United Kingdom, groups from major cities organize under banners like “Muslims Clean Up.” In Indonesia, the world’s largest Muslim-majority nation, youth groups tackle the monumental waste left after celebrations. In South Africa, Canada, the United States, and Germany, communities follow suit. This global synchrony underscores that the impulse is doctrinal, not political or local. It is a unified response from a global faith community to a global occurrence the universal celebration of the New Year and its universal side effect of waste. This wide scale adds immense weight to the action, positioning it as a significant, organized international movement of civic environmentalism rooted in faith.

Of course, the initiative also prompts broader reflections on our celebration habits, particularly regarding the environmental cost of New Year’s Eve fireworks. While the clean-up crews address the symptom, their work inevitably leads to conversations about the cause. The sight of volunteers collecting bags full of firework residue encourages public discourse on alternatives, such as drone light shows or more environmentally friendly pyrotechnics. In this way, the Muslim community’s service acts as a gentle catalyst for wider environmental awareness, pushing societies to consider how traditions can evolve to be more sustainable. The volunteers, by dealing with the physical aftermath, are indirectly advocating for a future where such clean-ups might be less necessary, where celebration does not come at such a high cost to the planet.

The narrative also powerfully counters prevailing negative stereotypes and Islamophobic tropes. In a media landscape where Muslim identity is often unfairly associated with negativity, the image of diverse Muslims voluntarily cleaning their shared cities presents a stark, beautiful contradiction. It showcases the faith’s emphasis on cleanliness, charity, and communal duty. It demonstrates that millions of ordinary Muslims are engaged in the quiet, humble work of making their neighborhoods better, an endeavor that is the very bedrock of a healthy society. This positive representation is vital, both for community self-esteem and for educating the broader public about the faith’s true, practice-oriented values that emphasize benefiting all of creation.

In the final analysis, the annual sight of Muslim communities gathering to clean the streets after the New Year’s Eve fireworks is more than just a feel-good story. It is a multifaceted lesson in practical faith, environmental ethics, and social harmony. It transforms the post-celebration litter, a symbol of transience and neglect, into an opportunity for lasting good. This movement beautifully marries the spiritual with the practical, proving that deep religious conviction can manifest in the most grounded, helpful ways. It builds bridges through brooms and garbage bags, fostering understanding through shared spaces and common goals. As the world continues to grapple with division and environmental crises, this simple, repeated act offers a hopeful template. It reminds us that after the loud, bright, and shared joy of celebration like the stunning but fleeting display of New Year’s Eve fireworks comes the quiet, enduring power of taking responsibility for our shared home, together. The clean-up is a silent, powerful prayer made action, a testament to the belief that faith is best expressed not only in words or rituals, but in tangible service to the community and care for the Earth we all inhabit.

Muslims Across The World Gather To Clean Up The Streets After New Year’s Celebrations

Yo, wanted to chime in about 66win9. This site is decent. They have a good variety of games, and navigation isn’t too bad either. Bonus structure isn’t the best, but it is functional. Worth a check on your own accord 66win9.